The chemical element tennessine is classed as a halogen. It was discovered in 2009 by a team of scientists led by Yuri Oganessian.

Data Zone

| Classification: | Tennessine is a halogen (presumed) |

| Color: | |

| Atomic weight: | (294), no stable isotopes |

| State: | solid (presumed) |

| Melting point: | |

| Boiling point: | |

| Electrons: | 117 |

| Protons: | 117 |

| Neutrons in most abundant isotope: | 177 |

| Electron shells: | 2, 8, 18, 32, 32, 18, 7 |

| Electron configuration: | [Rn] 5f14 6d10 7s2 7p5 (presumed) |

Reactions, Compounds, Radii, Conductivities

| Specific heat capacity | – |

| Heat of fusion | – |

| Heat of atomization | – |

| Heat of vaporization | – |

| 1st ionization energy | – |

| 2nd ionization energy | – |

| 3rd ionization energy | – |

| Electron affinity | – |

| Minimum oxidation number | – |

| Min. common oxidation no. | – |

| Maximum oxidation number | – |

| Max. common oxidation no. | – |

| Electronegativity (Pauling Scale) | – |

| Polarizability volume | – |

| Reaction with air | – |

| Reaction with 15 M HNO3 | – |

| Reaction with 6 M HCl | – |

| Reaction with 6 M NaOH | – |

| Oxide(s) | – |

| Hydride(s) | – |

| Chloride(s) | – |

| Atomic radius | – |

| Ionic radius (1+ ion) | – |

| Ionic radius (2+ ion) | – |

| Ionic radius (3+ ion) | – |

| Ionic radius (1- ion) | – |

| Ionic radius (2- ion) | – |

| Ionic radius (3- ion) | – |

| Thermal conductivity | – |

| Electrical conductivity | – |

| Freezing/Melting point: | – |

Six atoms of tennessine have been detected. Image Courtesy: Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

The heavy ion cyclotron U-400 in Dubna, where tennessine was synthesized.

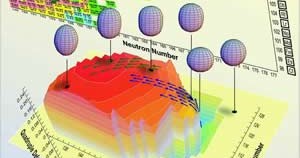

A combination of experiments and computer simulations enable predictions to be made of deformations and shapes of the heaviest elements in and beyond the current periodic table. Photo: ORNL.

Discovery of Tennessine

In 2009, the first atoms of element 117 were made in the Flerov Laboratory of Nuclear Reactions in Dubna, Russia. Evidence of the synthesis was published in April 2010, by scientific teams from Russia and the United States of America. (1), (2)

The research effort, led by Yuri Oganessian, was a collaboration between the Joint Institute of Nuclear Research (Dubna, Russia); the Research Institute for Advanced Reactors, Dimitrovgrad; Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory; Oak Ridge National Laboratory; Vanderbilt University, Tennessee; and the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

Further experiments and analysis later confirmed this result and the discovery was verified by IUPAC in 2015.

The element is named after the Tennessee region, in recognition of the contribution institutions from that American State played in superheavy element research.

Tennessine was made by a fusion reaction of element 20 with element 97: calcium-48 with berkelium-249.

In the first synthesis of tennessine, calcium ions were formed into a beam in a cyclotron (a particle accelerator) and fired at a target layer of berkelium deposited 300 nm thick on titanium foil.

The first bombardment lasted 70 days. The berkelium was bombarded with over 7 trillion calcium-48 ions per second, accelerated to about 10% of the speed of light.

The data showed five nuclei of interest were produced during the 70 day bombardment. As a consequence of the high energy of the impacts that created them, these nuclei instantly lost thermal energy by emitting four neutrons to form tennessine-293.

The tennessine-293 (approximate half-life 14 ms) decayed by alpha emission into element 115 (moscovium). (2), (3)

In a second bombardment lasting 50 days, the speed of the bombarding calcium-48 ions was reduced. The resulting impacts were of lower energy and the single nucleus of interest that formed needed to emit just three neutrons to lose its excess energy, leading to the heavier tennessine-294 isotope. The data showed one atom of tennessine-294 (approximate half-life 78 ms) was formed in the bombardment, decaying again to element 115.

As a result of its position in Group 17 of the periodic table, tennessine is expected to have chemical properties characteristic of the halogens. The effects of relativistic electrons, however, may result in partial metalloid properties.

Too little of the element has been synthesized for its chemical properties to be confirmed.

Jim Roberto from Oak Ridge said: “New isotopes observed in these experiments continue a trend toward higher lifetimes for increased neutron numbers, providing evidence for the proposed ‘island of stability’ for super-heavy nuclei.”

IUPAC has accepted the discoveries of:

- element 113 (nihonium)

- element 114 (flerovium)

- element 115 (moscovium)

- element 116 (livermorium)

- element 117 (tennessine)

- element 118 (oganesson)

completing the seventh row of the periodic table.

Appearance and Characteristics

Harmful effects:

Tennessine is harmful due to its radioactivity.

Characteristics:

Tennessine is a synthetic radioactive metal and has only been produced in minute amounts.

Uses of Tennessine

Tennessine is of research interest only.

Abundance and Isotopes

Abundance earth’s crust: nil

Abundance solar system: parts per trillion by weight, parts per trillion by moles

Cost, pure: $ per 100g

Cost, bulk: $ per 100g

Source: Tennessine can be produced by bombarding 249Bk with 48Ca in a heavy ion accelerator.

Isotopes: Initial data has identified 2 isotopes of tennessine, with mass numbers 293 and 294. Neither are stable. Tennessine-293’s approximate half-life is 14 ms and tennessine-294’s is 78 ms.

References

- Yu. Ts. Oganessian et al., Phys. Rev. Lett., 2010, 104, 142502, 4 pages.

- Office of Science, Nations Work Together to Discover New Element,.

- Press Release The Armenia Weekly.

Cite this Page

For online linking, please copy and paste one of the following:

<a href="https://www.chemicool.com/elements/ununseptium.html">Tennessine</a>

or

<a href="https://www.chemicool.com/elements/ununseptium.html">Tennessine Element Facts</a>

To cite this page in an academic document, please use the following MLA compliant citation:

"Tennessine." Chemicool Periodic Table. Chemicool.com. 14 Jun. 2016. Web. <https://www.chemicool.com/elements/ununseptium.html>.